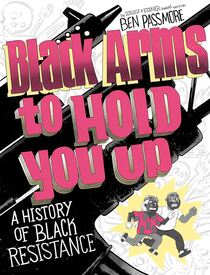

Beginning with the first impression – the juxtaposition of the book’s title, “Black Arms to Hold You Up” and its accompanying cover illustration of large, looming black arm(ament)s against a background of skeletons, between which the human actors are running in fear – it is clear right from the start that we are being presented with a multivalent and irony-rich agitprop work. It will be equally clear by the end that it is also a work capable of constructing new meaning through a masterful synthesis of image and text.

The phrase “to hold you up” in the title can have (at least) three possible meanings: 1) to physically hold you up, as in to keep you from falling; 2) to hold you up, as in to slow your progress; 3) and to hold you up in a robbery, as in “this is a hold up”.

A key conundrum being posed here, at the outset, is the question of the relationship between the organic natural protection offered by the arms of family and community and the artificial, manufactured “protection” offered by fire arms.

Black Arms opens with the protagonist/narrator stand-in for Passmore watching, on his phone, the video of Philando Castile’s murder by a police officer on July 6, 2016, to which the entire work may be seen as an eloquent response. Passmore then ventures into some of the lesser explored corners of (African-)American history and shines his light into the darkness of our national ignorance. Well over a century of historical terrain is covered – too much to really dig into here – beginning more-or-less at the conclusion of the American Civil War with a brief summation of the repeated organized White violence against Black efforts at self-determination in former slave-holding states in the wake of emancipation that is folded into an episode focusing on a specific instance of Black resistance fomented by the one-man army that was Robert Charles in the Louisiana of the first decade of the Twentieth Century. We then head to the post-WW II south with the rise of Robert F. Williams amidst the struggle of the NAACP against the violent oppression of the KKK, leading (somewhat indirectly) to the formation of 1960s Republic of New Afrika (RNA) which also involved Malcolm X’s widow, Betty Shabazz, Gaidi Obadele, and others, leading in turn (again, indirectly) to the advent of Assata Shakur (née JoAnne Chesimard), taking us into the 1970s and then on to 1980s with the infamous confrontation between MOVE and the City of Philadelphia before heading to the west coast for a look at “Monster” Kody (aka Sanyika Shakur) as an embodiment of L.A. gang culture, and then into the 21st century before, finally, looping back to the beginning with Micah Xavier Johnson’s killing of five Dallas police officers that was evidently triggered by Philando Castile’s murder the day before.

As you would expect from foregoing, these illuminated episodes each intersect at some point with violence and the use of fire arms, and Passmore is unstinting in his probing examinations and postmortems. Ultimately, Black Arms to Hold You Up posits a better way, one that is grounded in the study of history in the service of building a secure and sustainable community through the self-empowerment that knowledge brings.

The central narrative device that Passmore employs to explore his theme – that of a time-traveling narrator – is particularly successful. While other cartoonists presenting historical events in comics have employed the technique of vacillating between depictions of their present selves and the historical events they are recounting – notably Art Spiegelman and Joe Sacco – Passmore’s technique of actually inserting himself into the historical setting, in the capacity of a (for the most part) passive actor, introduces a playful element that allows him to bring his wry skepticism and disarming humor into his representation of the series of historical events that make up the bulk of the narrative.

Working to keep a contemporary perspective on past events present also avoids the pitfalls of presenting images of the past as self evident. Explicitly showing the presence of a contemporary perspective on past events avoids the illusion of their absence. This demonstrates how the process of discovering the ways in which the past is present in us – through the reading and exploration of history – necessarily involves the projecting of our present selves into that past.

This further enables Black Arms to function simultaneously as history and memoir, creating a dialectic between the factual existence of the past and the personal interpretation of it in a manner that is brought into being by the formal qualities of the comics medium.

We've posted some images from the book HERE to provide some sense of how this all is accomplished.

The book concludes with a powerful coda asserting that the pen (which we comics readers know can draw as well as write) is mightier than the sword (read here as gun), followed by a substantial bibliography for further reading to help bolster the hermeneutic front of this ongoing struggle.

To anyone who feels like getting a head start, we suggest Ida B. Wells’s 1893 speech, “Lynch Law in All Its Phases”, available in its entirety HERE.