FROM THE ARCHIVE

ONE BRAND NEW FACTPORY SEALED COPY

Prestel sez:

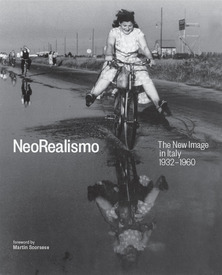

This stunning book explores Italian Neorealism in photography, as it documented Italy’s economic and social conditions in the mid-20th century and its rise as a democratic nation.Originally used for Fascist propaganda, the camera in Italy became a tool for artists to reveal the poverty and oppression of their country and a way to instigate positive social development and create a national identity. The NeoRealismo style became a call for economic justice as well as an artistic movement that influenced the modern world. The achievements of that movement are celebrated in this book with more than 200 illustrations, including exquisitely reproduced photographs and magazine images as well as film stills and posters. Together these images portray the seismic changes that took place throughout Italy during and after the war. The migration from south to north, the rural and urban poverty, and the desire to establish a national identity are all given expression through the photographers’ lenses. Accompanying essays discuss the technological changes that transformed the country, trace the evolution of Neorealist cinema, and explore how writers became part of this revolution. Beautiful, raw, and free of artifice, these images and the people who created them ushered a unique and fascinating moment in modern art history.

With a foreword from Martin Scorsese With contributions from Fabio Amodeo, Gian Piero Brunetta, Bruno Falcetto, Giuseppe Pinna Hardcover, 352 pages, 24,0 x 29,0 cm, 9.4 x 11.4 in, 241 b/w illustrations ISBN: 978-3-7913-5769-0Here's a description of the show ar the Greyt Art Museum at NYU that this book seves as the catalogue for:

NeoRealismo: The New Image in Italy, 1932–1960 poignantly portrays life in Italy through the lens of photography before, during, and after World War II. As both a formal approach and a mindset, neorealism reached the height of its popularity in the 1950s. While the movement is primarily associated with cinematic and literary depictions of dire postwar conditions, this exhibition draws attention to the period’s many photographers and their diverse approaches to the medium. Featuring some 175 images by over 60 Italian photographers, NeoRealismo documents not only Italy’s economic and social conditions in the mid-20th century but its rebirth as a democratic nation.

Installed thematically, NeoRealismo opens with Realism in the Fascist Era, which traces the regime’s use of photography as an instrument of communication that reached the masses despite widespread illiteracy. By the end of the war, Italy was in ruins. Poverty and Reconstruction conveys how photographers, along with filmmakers, documented the difficult conditions of everyday life while also communicating the country’s sense of vitality and its hopes for the future.

After the fall of Fascism, Italy remained fragmented. Ethnographic Investigation chronicles how photographers traveled to every corner of the peninsula, portraying the country’s many faces in order to rebuild a collective identity through individual differences and intimate gestures. Photojournalism and the Illustrated Press highlights neorealism’s golden age, when photographers were often hired to work on editorial teams, and when photographic narratives in newspapers and magazines came to resemble cinematography, with multiple-page spreads, special supplements, and serialized articles. The exhibition concludes with From Art to Document, which illuminates the establishment of photo clubs where members hotly debated the creative value of the medium, laying the foundations for photographic criticism in Italy. Two opposing schools arose. For some, neorealism represented a rigid approach that stifled free expression. For others, photography that did not retain a connection to real life risked becoming a formal exercise appreciated by only a select few.

NeoRealismo references key films via clips and movie posters. As director Martin Scorsese observes, neorealism is a “collective human response to the devastation and tragedy of war, a response that came in the form of art. It is an impulse . . . a moment. It is an act of recovery and restoration.” Pairing gelatin silver prints with the formats in which the images originally circulated—illustrated magazines, photo books, and exhibition catalogues—NeoRealismo reveals how Italian photographers captured the seismic changes that ushered in a fascinating period of modern history.